Opinion: The Era of the Stablecoin Duopoly Is Coming to an End

The article analyzes the underlying reasons why the duopoly of Circle (USDC) and Tether (USDT), which still dominate about 85% of the stablecoin market, is beginning to break down. It points out that various structural changes are driving the stablecoin market toward "substitutability," challenging the core advantages of the existing giants.

Translated by: Saoirse, Foresight News

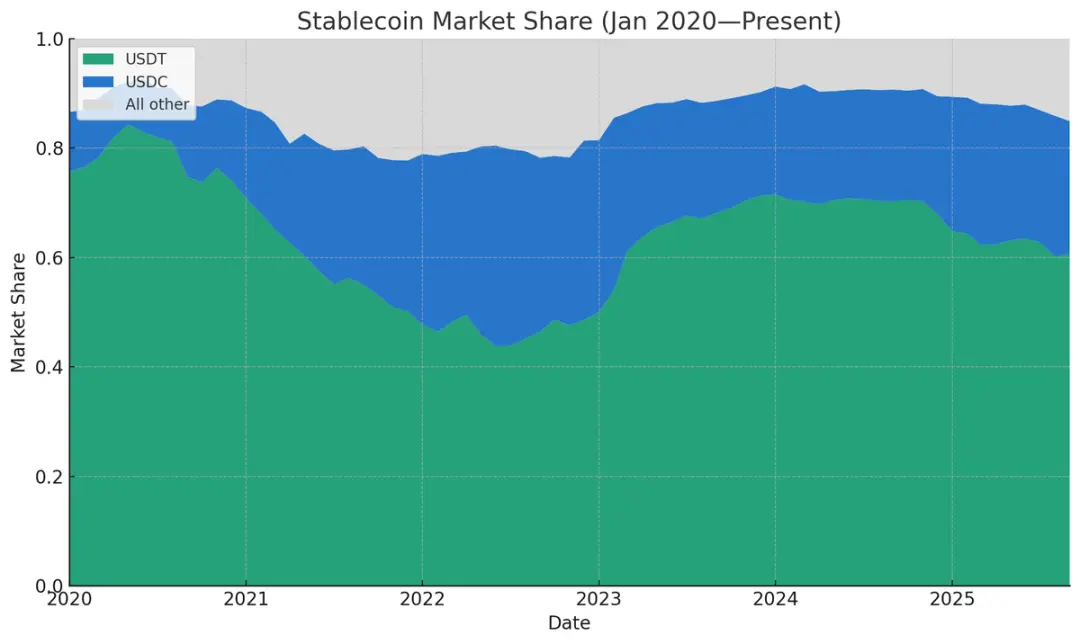

Circle's equity valuation has reached $30.5 billions. Reportedly, the parent company of Tether (issuer of USDT) is currently raising funds at a $500 billions valuation. At present, the total supply of these two major stablecoins has soared to $245 billions, accounting for about 85% of the entire stablecoin market. Since the inception of the stablecoin industry, only Tether and Circle have consistently maintained significant market share, with other competitors struggling to keep up:

-

Dai’s market cap peaked at only $10 billions at the beginning of 2022;

-

Terra ecosystem’s UST once surged to $18 billions in May 2022, but its market share was only about 10%, and it was short-lived, ultimately collapsing;

-

The most ambitious challenger was Binance-issued BUSD, which peaked at $23 billions in late 2022 (15% market share), but was subsequently shut down by the New York Department of Financial Services (NYDFS).

Relative supply share of stablecoins (Data source: Artemis)

The lowest combined market share I could find for Tether and Circle was 77.71% in December 2021—at that time, Binance USD, DAI, FRAX, and PAX together had a considerable market share. (If you go back before Tether’s creation, of course, there was no market share for it, but earlier mainstream stablecoins like Bitshares and Nubits have not survived to this day.)

In March 2024, the dominance of these two giants peaked, accounting for 91.6% of the total stablecoin supply, but has been declining ever since. (Note: The market share here is calculated by supply, as this metric is easy to track; if calculated by transaction volume, number of trading pairs, real-world payment scale, or number of active addresses, their share would undoubtedly be even higher.) As of now, the two giants’ market share has dropped from last year’s peak to 86%, and I believe this trend will continue. The reasons include: increased willingness of intermediaries to issue their own stablecoins, intensifying “race to the bottom” in stablecoin yields, and new regulatory changes following the introduction of the GENIUS Act.

Intermediaries Are Issuing Their Own Stablecoins

In the past few years, if you wanted to issue a “white-label stablecoin” (i.e., a stablecoin customized based on an existing technology framework), you not only had to bear very high fixed costs, but also had to rely on Paxos (a compliant fintech company). But now, the situation has completely changed: current options for issuance partners include Anchorage, Brale, M0, Agora, and Bridge under Stripe, among others. In our portfolio, some seed-stage startups have already successfully launched their own stablecoins through Bridge—there’s no need to be an industry giant to get involved in stablecoin issuance.

Bridge co-founder Zach Abrams explained the rationale for self-issuing stablecoins in his article on “open issuance”:

For example, if you use an off-the-shelf stablecoin to build a new type of bank, you’ll face three major problems: a) you can’t fully capture yields to build a high-quality savings account; b) you can’t customize the reserve asset portfolio, making it hard to balance increased liquidity with higher returns; c) when withdrawing your own funds, you have to pay a 10 basis point (0.1%) redemption fee!

His points are very valid. If you use Tether, you can hardly obtain any yield to pass on to customers (and nowadays, customers generally expect some yield when depositing funds); if you use USDC, you might get some yield, but you have to negotiate a revenue share with Circle, which will take a cut. Additionally, using third-party stablecoins comes with many restrictions: you can’t independently decide freeze/seizure policies, you can’t choose which blockchain network the stablecoin is deployed on, and redemption fees may rise at any time.

I once believed that network effects would dominate the stablecoin industry, and that only one or two mainstream stablecoins would remain in the end. But now my view has changed: cross-chain swap efficiency is improving, and swapping between different stablecoins on the same blockchain is becoming increasingly convenient. In the next year or two, many crypto intermediaries may display user deposits as generic “dollars” or “dollar tokens” (rather than explicitly labeling them as USDC or USDT), and guarantee that users can redeem them for any stablecoin of their choice.

Currently, many fintech companies and neobanks have adopted this model—they prioritize product experience over sticking to crypto industry traditions, so they display user balances as “dollars” and manage reserve assets on the backend themselves.

For intermediaries (whether exchanges, fintech companies, wallet providers, or DeFi protocols), there is a strong incentive to move user funds from mainstream stablecoins to their own stablecoins. The reason is simple: if a crypto exchange holds $500 millions in USDT deposits, Tether can earn about $35 millions per year from the “float” (i.e., idle funds), while the exchange gets nothing. There are three ways to turn this “idle capital” into revenue:

-

Request the stablecoin issuer to share part of the yield (for example, Circle shares revenue with partners through reward programs, but as far as I know, Tether does not share yield with intermediaries);

-

Cooperate with emerging stablecoins (such as USDG, AUSD, USDe issued by Ethena, etc.), which are designed with revenue-sharing mechanisms;

-

Issue their own stablecoins and internalize all the yield.

For example, if an exchange wants to persuade users to abandon USDT and use its own stablecoin, the most direct strategy is to launch a “yield program”—such as paying users yields based on US short-term Treasury rates, while retaining 50 basis points (0.5%) of profit for itself. For fintech products serving non-crypto-native users, there’s not even a need to launch a yield program: just display user balances as generic dollars, automatically convert funds into their own stablecoin on the backend, and convert to Tether or USDC as needed when users withdraw.

Currently, this trend is gradually emerging:

-

Fintech startups generally adopt the “generic dollar display + backend reserve management” model;

-

Exchanges are actively reaching revenue-sharing agreements with stablecoin issuers (for example, Ethena has successfully promoted its USDe on multiple exchanges through this strategy);

-

Some exchanges have formed stablecoin alliances, such as the “Global Dollar Alliance,” whose members include Paxos, Robinhood, Kraken, Anchorage, etc.;

-

DeFi protocols are also exploring their own stablecoins, with the most typical case being Hyperliquid (a decentralized exchange): it selected a stablecoin issuance partner through a public bidding process, with the clear goal of reducing reliance on USDC and capturing reserve asset yields. Hyperliquid received bids from Native Markets, Paxos, Frax, and others, ultimately choosing Native Markets (a decision that was controversial). Currently, Hyperliquid’s USDC balance is about $5.5 billions, accounting for 7.8% of USDC’s total supply—although Hyperliquid’s USDH cannot replace USDC in the short term, this public bidding process has damaged USDC’s market image, and more DeFi protocols may follow suit in the future;

-

Wallet providers have also joined the self-issuance trend, such as Phantom (a mainstream wallet in the Solana ecosystem), which recently announced the launch of Phantom Cash—a stablecoin issued by Bridge, featuring built-in yield and debit card payment functions. Although Phantom cannot force users to use this stablecoin, it can incentivize users to migrate through various means.

In summary, as the fixed costs of stablecoin issuance decrease and revenue-sharing models become more common, intermediaries no longer need to give up float yield to third-party stablecoin issuers. As long as they are large enough and reputable enough to earn user trust in their white-label stablecoins, self-issuance becomes the optimal choice.

Intensifying “Race to the Bottom” in Stablecoin Yields

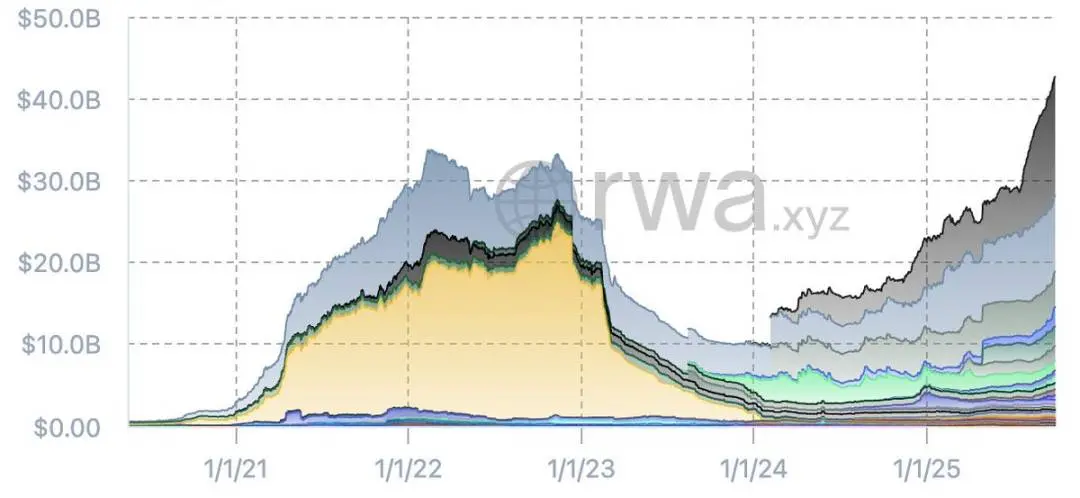

If you look at the stablecoin supply chart excluding Tether and USDC, you’ll see that the market landscape for “other stablecoins” has changed significantly in recent months. In 2022, there was a wave of short-lived popular stablecoins (such as Binance BUSD and Terra UST), but after the Terra collapse and the credit crisis, the industry underwent a reshuffle, and a batch of new stablecoins emerged from the “ruins.”

Stablecoin supply excluding USDT and USDC (Data source: RWA.xyz)

Currently, the total supply of non-Tether/Circle stablecoins has reached a record high, and issuers are more dispersed. The main emerging stablecoins in the market now include:

-

Sky (the upgraded version of Dai launched by MakerDAO);

-

USDe issued by Ethena;

-

PYUSD issued by Paypal;

-

USD1 issued by World Liberty.

In addition, new stablecoins such as USDY by Ondo, USDG by Paxos (as an alliance member), and AUSD by Agora are also worth watching. In the future, there will also be bank-issued stablecoins entering the market. Existing data already shows the trend: compared to the previous stablecoin boom, there are now more credible stablecoins on the market, and the total supply has surpassed that of the last bull market—even though Tether and Circle still dominate market share and liquidity.

These new stablecoins share a common feature: they generally focus on “yield transmission.” For example, Ethena’s USDe obtains yield through crypto basis trading and passes part of the yield to users; its supply has already soared to $14.7 billions, making it the most successful emerging stablecoin this year. In addition, USDY by Ondo, SUSD by Maker, USDG by Paxos, and AUSD by Agora all have revenue-sharing mechanisms built in from the start.

Some may question: “The GENIUS Act prohibits stablecoins from providing yield.” In a sense, this is true, but if you pay attention to the exaggerated statements of recent bank lobbying groups, you’ll see that this issue is far from settled. In fact, the GENIUS Act does not prohibit third-party platforms or intermediaries from paying rewards to stablecoin holders—and the source of these rewards is the yield paid by issuers to intermediaries. Mechanistically, it’s even impossible to close this “loophole” through policy language, nor should it be closed.

With the advancement and implementation of the GENIUS Act, I’ve noticed a trend: the stablecoin industry is shifting from “directly paying yield to holders” to “transmitting yield through intermediaries.” For example, the cooperation between Circle and Coinbase is a typical case—Circle pays yield to Coinbase, which then passes part of the yield to users holding USDC, and this model shows no sign of stopping. Almost all new stablecoins have built-in yield strategies, and the logic is clear: if you want to persuade users to abandon highly liquid and widely recognized Tether in favor of a new stablecoin, you must provide a sufficiently attractive reason (yield is the core attraction).

I predicted this trend at the 2023 TOKEN2049 Global Crypto Summit, and although the introduction of the GENIUS Act delayed the timeline, it is now clearly emerging.

For less flexible incumbents (Tether and Circle), this “yield-oriented” competitive landscape is undoubtedly unfavorable: Tether provides no yield at all, Circle only shares yield with a few institutions like Coinbase, and its relationships with other institutions are unclear. In the future, emerging startups may squeeze the market space of mainstream stablecoins through higher yield sharing, creating a “race to the bottom” in yields (actually a “race to the top” in yield caps). This pattern may benefit institutions with scale advantages—just as the ETF industry once experienced a “race to zero fees,” ultimately forming a duopoly of Vanguard and BlackRock. But the question is: if banks eventually enter the game, can Tether and Circle still be the winners?

Banks Can Now Officially Participate in Stablecoin Business

After the implementation of the GENIUS Act, the Federal Reserve and other major financial regulators have adjusted relevant rules—banks can now issue stablecoins and conduct related business without applying for a new license. However, according to the GENIUS Act, bank-issued stablecoins must comply with the following rules:

-

100% collateralized by high-quality liquid assets (HQLA);

-

Support 1:1 on-demand redemption for fiat currency;

-

Fulfill disclosure and audit obligations;

-

Accept supervision by relevant regulatory agencies.

At the same time, bank-issued stablecoins are not considered “deposits protected by federal deposit insurance,” and banks are not allowed to use the collateral assets of stablecoins for lending.

When banks ask me “should we issue a stablecoin,” my usual advice is “don’t bother”—just integrate existing stablecoins into core banking infrastructure, no need to issue directly. Even so, some banks or bank alliances may consider issuing stablecoins, and I believe we will see such cases in the next few years. The reasons are as follows:

-

Although stablecoins are essentially “narrow banking” (only taking deposits, not lending), which may reduce bank leverage, the stablecoin ecosystem can bring multiple revenue opportunities, such as custody fees, transaction fees, redemption fees, API integration service fees, etc.;

-

If banks find that deposits are being lost to stablecoins (especially those that can provide yield through intermediaries), they may issue their own stablecoins to stop the trend;

-

For banks, the cost of issuing stablecoins is not high: there is no need to hold regulatory capital for stablecoins, and stablecoins are “fully reserved, off-balance-sheet liabilities,” with lower capital intensity than ordinary deposits. Some banks may consider entering the “tokenized money market fund” field, especially given Tether’s continued profitability.

In extreme cases, if the stablecoin industry completely bans yield sharing and all “loopholes” are closed, issuers will gain “seigniorage-like rights”—for example, collecting 4% asset yield without paying any return to users, which is even more lucrative than the net interest margin of “high-yield savings accounts.” But in reality, I don’t think the yield “loophole” will be closed, and issuers’ profit margins will gradually decline over time. Even so, for large banks, as long as they can convert part of their deposits into stablecoins, even retaining just 50-100 basis points (0.5%-1%) of profit can bring considerable income—after all, large banks’ deposit scales can reach trillions of dollars.

In summary, I believe banks will eventually join the stablecoin industry as issuers. Earlier this year, The Wall Street Journal reported that JPMorgan, Bank of America (BoFA), Citi, and Wells Fargo have already held preliminary talks about forming a stablecoin alliance. For banks, the alliance model is undoubtedly the optimal choice—a single bank can hardly build a distribution network strong enough to compete with Tether, while an alliance can pool resources and enhance market competitiveness.

Conclusion

I once firmly believed that the stablecoin industry would eventually be left with only one or two mainstream products, at most no more than six, and repeatedly emphasized that “network effects and liquidity are king.” But now I’m starting to reconsider: can stablecoins really benefit from network effects? They are different from businesses like Meta, X (formerly Twitter), or Uber that rely on user scale—the real “network” is the blockchain, not the stablecoin itself. If users can move in and out of stablecoins frictionlessly, and cross-chain swaps are convenient and low-cost, the importance of network effects will be greatly reduced. When exit costs approach zero, users will not be forced to stick to a particular stablecoin.

It’s undeniable that mainstream stablecoins (especially Tether) still have a core advantage: among hundreds of exchanges worldwide, their trading spreads (bid-ask spreads) with major forex pairs are extremely low, which is hard to surpass. But now, more and more service providers are starting to offer “wholesale FX rates” (i.e., interbank rates), enabling stablecoin-to-local fiat conversions both on and off exchanges—as long as the stablecoin is credible, these providers don’t care which one is used. The GENIUS Act has played an important role in standardizing stablecoin compliance, and the maturity of infrastructure benefits the entire industry—except for the existing giants (Tether and Circle).

Multiple factors are gradually breaking the Tether and Circle duopoly: more convenient cross-chain swaps, near-free intra-chain stablecoin swaps, clearinghouses supporting cross-stablecoin/cross-chain transactions, and the GENIUS Act promoting the homogenization of US stablecoins—all these changes reduce the risk for infrastructure providers holding non-mainstream stablecoins and drive stablecoins toward “fungibility,” which is of no benefit to the current giants.

Now, the emergence of numerous white-label issuers has lowered the cost of stablecoin issuance; non-zero Treasury yields are incentivizing intermediaries to internalize float yield, squeezing out Tether and Circle; fintech wallets and neobanks are leading the way, with exchanges and DeFi protocols following closely—every intermediary is eyeing user funds, thinking about how to turn them into their own revenue.

Although the GENIUS Act restricts stablecoins from directly providing yield, it does not completely block the path of yield transmission, giving new stablecoins room to compete. If the yield “loophole” persists, a “race to the bottom” in revenue sharing will be inevitable, and if Tether and Circle respond slowly, their market position may be weakened.

In addition, we must not ignore the “off-market giants”—financial institutions with balance sheets in the trillions of dollars. They are closely watching whether stablecoins will trigger deposit outflows and how to respond. The GENIUS Act and regulatory adjustments have opened the door for banks to enter. Once banks formally participate, the current stablecoin market cap of about $300 billions will seem insignificant. The stablecoin industry is only 10 years old—the real competition is just beginning.

Original link

Disclaimer: The content of this article solely reflects the author's opinion and does not represent the platform in any capacity. This article is not intended to serve as a reference for making investment decisions.

You may also like

Do Kwon Wants Lighter Sentence After Admitting Guilt

Bitwise Expert Sees Best Risk-Reward Since COVID

Stellar (XLM) Price Prediction: Can Bulls Push Toward $0.30 in December?

21Shares XRP ETF Set to Launch on 1 December as ETF Demand Surges